Wheat is the foundation of global nutrition: more than 35 percent of the world’s population depends on this grain for their daily caloric intake. However, climate change is putting pressure on this staple crop, with effects increasingly evident in the planet’s major production basins.

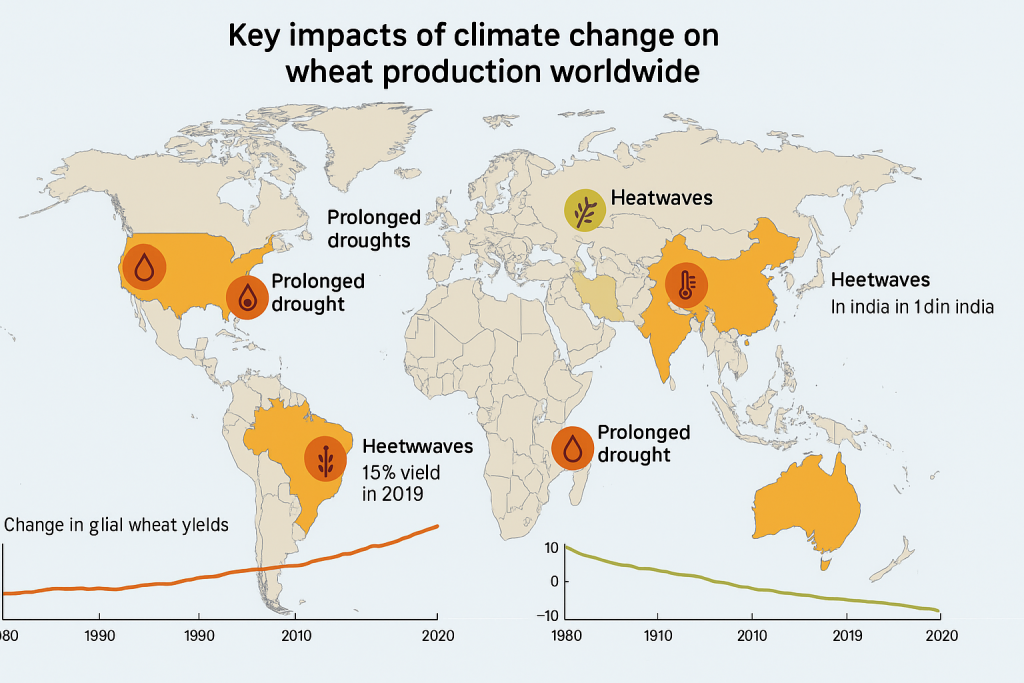

One of the most significant impacts is the increasing frequency of prolonged droughts. Grain-growing areas such as the U.S. Midwest, southern Australia, the Mediterranean basin, and central Asia are facing increasingly dry seasons, with heavy impacts on yields. Soft wheat, in particular, suffers most from water shortages, and in some regions production losses of up to 40% have been reported in exceptionally dry years. To address this challenge, solutions such as the adoption of less water-demanding varieties, precision irrigation techniques and genetic selection geared toward drought tolerance are being tested.

Heat waves also pose a real threat, especially when they strike at critical stages such as flowering and grain growing. In India, for example, some areas are already experiencing yield declines of 10-15 percent due to spring temperature spikes. To adapt, farmers are altering planting calendars, selecting more heat-resistant varieties, and experimenting with agronomic strategies to reduce direct crop exposure.

Global warming then has an indirect but equally dangerous effect: the expansion of plant diseases and pests into areas where they were not previously present. Fungal diseases such as wheat rusts (e.g., Puccinia graminis), ear fusarium, and new harmful insects such as aphids and thrips are becoming more prevalent. Climate change is also altering the effectiveness of phytosanitary treatments, making agronomic defense more complex. In response, satellite monitoring techniques, the use of predictive models and integrated crop management are being refined.

The resilience of wheat production, however, is also being built through more sustainable agricultural practices. In many areas, the focus is on diversification of crop varieties, longer crop rotations, and collaborative networks among farmers, which allow the exchange of data, experiences, and local solutions. Farmers are becoming true climate sentinels, capable of adapting season after season.

According to the FAO, up to 60% of projected global wheat losses by 2050 will be attributable to drought and heat. A study published in Nature Climate Change estimates that for every additional degree Celsius, global wheat yields could decrease between 4 and 6 percent.

Climate change is not a future threat, but a present reality that is already rewriting the world’s grain geography. The challenge is to make the agricultural system more flexible, local and adaptive. In this scenario, grain producers will play a central role in the transition to more resilient agriculture. The future of global food will also depend on how well we can sustain these changes, with conscious choices and targeted policies.

Sources:

– Home | Climate change | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

– Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability | Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

– Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability | Nature Communications

– Wheat breeding strategies for increased climate resilience – CIMMYT

– JRC Publications Repository – European Drought Risk Atlas